Malaria: Prevention and Cure

Prevention and Cure

Malaria prevention needs to be approached from two fronts: protecting against infection and reducing the development of the disease in infected people.

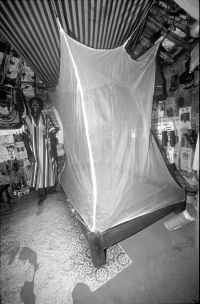

Protective measures against the mosquito have been used for hundreds of years. The inhabitants of swampy regions in ancient Egypt were known to sleep in tower-like structures out of the reach of mosquitoes; others slept under nets. Current measures that protect against infection are still mosquito-focused, like protective clothing, repellents, bed nets, or mosquito control programs. Studies in Ghana, Kenya, and other African nations show that about 30 percent of child deaths could be avoided if children slept under bed nets regularly treated with insecticides.

Mosquito bed net installed in a hut in the village of Kiyi, Kuje, near Abuja, Nigeria. (© WHO/Pierre Viyot)

Clinic worker in Kiyi Village showing villagers how to soak a bed net in insect repellant. (© WHO/Pierre Viyot)

The discovery of the insecticide DDT in 1942 and its first use in Italy in 1944 made the ideal of global eradication of malaria seem possible. In the 1950s and 1960s, DDT lowered malaria rates in many parts of the world. However, due to environmental toxicity, it was abandoned. Predictably, malaria rates increased. DDT has been replaced by newer insecticides, which have fewer health risks.

Disease management through early diagnosis and prompt treatment is fundamental to malaria control. Even with the emergence of drug resistance, malaria is largely a curable disease.

Efforts to Combat Malaria

Malaria eradication has been a priority for the World Health Organization (WHO) since its founding in 1948.

The hope of global eradication of malaria was abandoned in 1969. The virus's and the mosquito carrier's ability to develop resistance to drugs and insecticides has contributed to the failure, but social and political factors were, and remain, the biggest barriers. Despite the setbacks, many countries, including Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, Spain, Poland, Italy, Netherlands, and Portugal, eradicated endemic malaria.

A Malaria Vaccine?

The continued existence of malaria, caused by both drug-susceptible and drug-resistant parasites, indicates the need to develop a vaccine to control this disease. Today, there is no generalized vaccine for malaria. This may not be a surprise given the mosquito-host-parasite complexity; however, this complexity provides an opportunity to stop the disease at different stages.

There is optimism that a vaccine is possible, because people living in endemic areas develop immunity to the disease after repeated exposures. Once infected, people rarely develop severe cases of malaria after the age of ten, even though they may carry the parasites in their blood or liver. This immunity is specific for a given strain and wanes rapidly once a person leaves a specific area. Naturally acquired immunity appears to reflect a balance between the parasite and the host's immune system.

Antigen Alert

Malaria is a treatable disease, and yet it still kills over a million people each year. It is not the medical capability that is missing. In most countries, it is a lack of money and lack of an effective public health system to deliver and administer drugs effectively.

An ideal malaria vaccine would prevent infection by stimulating the immune system to destroy all parasites, whether free-swimming in the blood, in the liver, or in red blood cells.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Dangerous Diseases and Epidemics © 2002 by David Perlin, Ph.D., and Ann Cohen. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.