Mosquito and Tick-Borne Diseases: Dengue

Dengue

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS) occur in more than 100 countries and territories. The disease is endemic in Africa, the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, and most prominent in South East Asia and the Western Pacific. In the last 25 years, the number of countries with DHF has increased more than fourfold. In 1998, 1.2 million cases of dengue and DHF were reported to WHO, accounting for 15,000 deaths.

The number of reported cases is believed to represent only a very small percentage of the global disease, which by some accounts may top 51 million infections each year and has the potential to impact two fifths of the world's population.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever causes death in more than 20 percent of cases of the disease when medical attention is unavailable. That percentage can be reduced to less than 1 percent, however, with modern medical intervention. The same mosquito that carries the yellow fever virus can carry the dengue virus as well. The global rise in urban populations is bringing large numbers of people into contact with infected mosquitoes.

What Causes Dengue

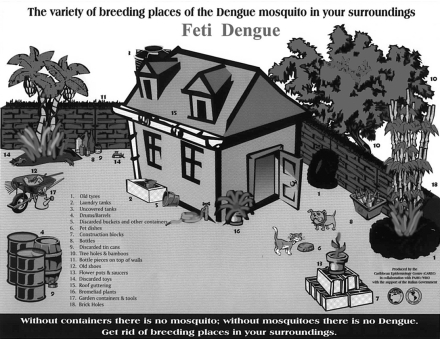

Dengue is a virus that is closely related to the yellow fever virus. Dengue, however, comes in four “flavors,” with the different types causing different forms of disease, ranging from mild to life-threatening. The mosquito that carries it breeds in fresh water in both natural and artificial containers, in and around human dwellings, wherever standing water may accumulate.

Where the mosquitoes that cause dengue can breed. (Courtesy PAHO)

What Dengue Feels Like

Dengue virus infection may cause a mild illness, dengue fever, or dengue hemorrhagic fever, including dengue shock syndrome. The severity of the disease depends on age, immune status, and the virus strain. Infants and children usually develop mild symptoms with fever similar to other viral infections. Most cases of dengue are benign and end after about seven days.

Dengue fever in older children and adults is characterized by a sudden onset of high fever, severe headache, muscle aches, intense muscle and joint pain (break-bone fever), nausea, weakness, vomiting, and rash. A measles-like rash shows up three to four days after the start of the symptoms and begins on the torso, spreading out to the face, arms, and legs. Fever and rash may subside, and then reoccur. All these symptoms usually persist for about seven days. The liver may also be enlarged in 10 percent of children.

The hemorrhagic form of dengue fever is much more severe and is associated with loss of appetite, vomiting, high fever, headache, and abdominal pain. Bleeding develops in the gums, skin, and intestinal tract, leading to a sudden drop in blood pressure with the onset of shock, circulatory failure, and in some cases, death.

Are You Likely to Get It?

Antigen Alert

Risk factors for dengue hemorrhagic fever include having antibodies to dengue virus from prior infection, age less than 12 years old, being female, being Caucasian, and not having good nutrition.

People infected with one type of virus maintain lifelong immunity to that type, but remain susceptible to infection with other strains of dengue. Severe disease is more likely to develop if a person was previously infected with one type, or was born to a dengue-immune mother.

Four different dengue viruses have been implicated in both dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Dengue hemorrhagic fever occurs when the patient contracts a different dengue virus after previous infection(s) by another type. Prior exposure to a different dengue virus type actually makes people more susceptible to dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome.

Worldwide, over 100 million cases of dengue fever occur every year. A small percent develop into dengue hemorrhagic fever. Most cases in the United States are brought in from other countries. It is possible to pass the infection from a traveler in the United States to someone who has not traveled.

Determining If You Have It

A positive diagnosis can be made with a blood test that looks for an antibody response to infection. Antibodies can be detected within six or seven days of onset of illness.

Waiting Out the Disease

There is no specific treatment for dengue fever. Typically, patients are given fluids and acetaminophen for fever and pain. Hospitalization is required if hemorrhagic fever or shock develops. Careful clinical management by health professionals can save the lives of dengue hemorrhagic fever patients.

The Catch-22 of Immunization

Because protection against only one dengue virus may actually increase the risk of the more serious disease, developing of a vaccine for dengue is very complicated and difficult. Right now, there is no vaccine available.

The only effective method of controlling or preventing dengue is to reduce the population of mosquitoes—vectors—that carry it. Vector control involves using environmental management and pesticides on larval habitats. During outbreaks, emergency control measures may also include widespread spraying of insecticide to kill adult mosquitoes. However, such approaches are short-lived. Regular monitoring and surveillance of the natural mosquito population are important for overall prevention.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Dangerous Diseases and Epidemics © 2002 by David Perlin, Ph.D., and Ann Cohen. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.