Palestine (Disputed) | Facts & Information

- Palestine (Disputed) Profile

- History

- News and Current Events

Infoplease has everything you need to know about Palestine (Disputed). Check out our country profile, full of essential information about Palestine (Disputed)'s geography, history, government, economy, population, culture, religion and languages. If that's not enough, click over to our collection of world maps and flags.

Plus, test your country knowledge with our Middle Eastern history and geography quiz, and see How Well Do You Know Palestine?

Facts & Figures

Geography

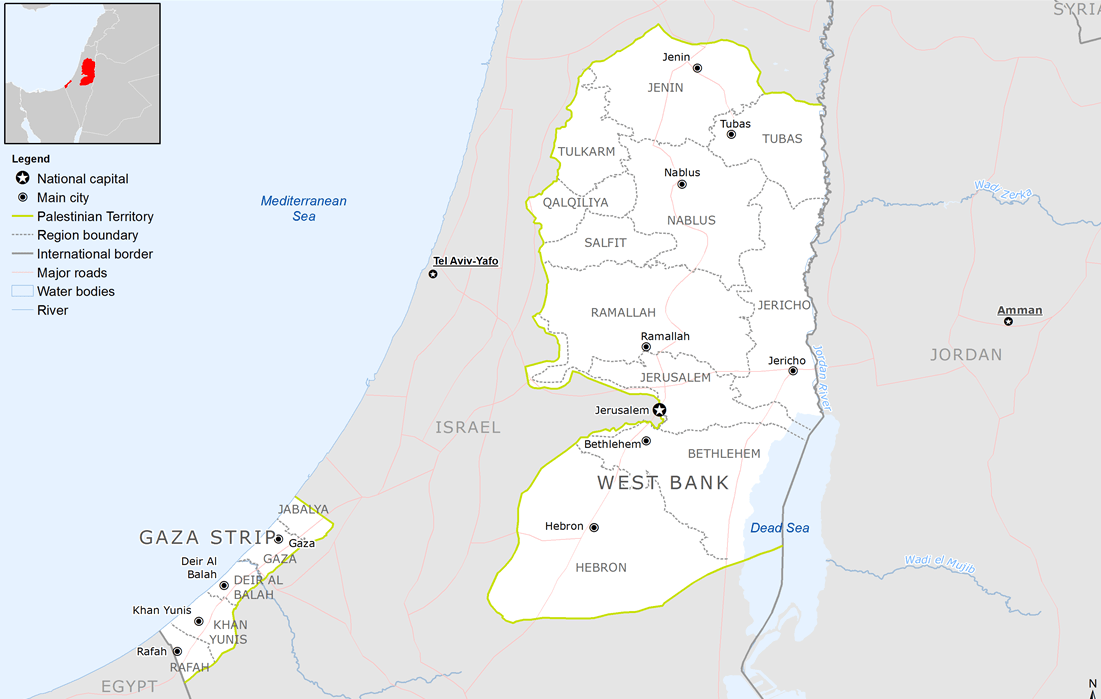

The West Bank is located to the east of Israel and the west of Jordan. The Gaza Strip is located between Israel and Egypt on the Mediterranean coast.

Government

The Palestinian Authority (PA), with Yasir Arafat its elected leader, took control of the newly non-Israeli-occupied areas, assuming governmental duties in 1994.

History

The history of the proposed modern Palestinian state, which is expected to be formed from the territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, began with the British Mandate of Palestine. From Sept. 29, 1923, until May 14, 1948, Britain controlled the region, but by 1947, Britain had appealed to the UN to solve the complex problem of competing Palestinian and Jewish claims to the land. In Aug. 1947, the UN proposed dividing Palestine into a Jewish state, an Arab state, and a small international zone. Arabs rejected the idea. As soon as Britain pulled out of Palestine in 1948, neighboring Arab nations invaded, intent on crushing the newly declared State of Israel. Israel emerged victorious, affirming its sovereignty. The remaining areas of Palestine were divided between Transjordan (now Jordan), which annexed the West Bank, and Egypt, which gained control of the Gaza Strip.

Through a series of political and social policies, Jordan sought to consolidate its control over the political future of Palestinians and to become their speaker. Jordan even extended citizenship to Palestinians in 1949; Palestinians constituted about two-thirds of the country's population. In the Gaza Strip, administered by Egypt from 1948–1967, poverty and unemployment were high, and most of the Palestinians lived in refugee camps.

In the Arab-Israeli War of 1967, Israel, over a period of six days, defeated the military forces of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan and annexed the territories of East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and all of the Sinai Peninsula. The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), formed in 1964, was a terrorist organization bent on Israel's annihilation. Palestinian rioting, demonstrations, and terrorist acts against Israelis became chronic. In 1974, PLO leader Yasir Arafat addressed the UN General Assembly, the first stateless government to do so. Violence again escalated in 1987 during the intifada (“shaking off”), a new era in Palestinian mass mobilization. In 1988, Yasir Arafat publicly eschewed terrorism and officially recognized the state of Israel.

The Oslo Accord, Government Corruption, and a "Road Map" to Peace

In 1993, highly secretive talks in Norway between the PLO and the Israeli government resulted in the Oslo Accord. The accord stipulated a five-year plan in which Palestinians of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip would gradually become self-governing. On Sept. 13, 1993, Arafat and Israeli prime minister Yitzak Rabin signed the historic “Declaration of Principles.” As part of the agreement, Israel pulled out of the Gaza Strip and Jericho in the West Bank in 1994. The Palestinian Authority (PA), with Arafat as its elected leader, took control of the newly non-Israeli-occupied areas, assuming all governmental duties.

Intensive negotiations between Israel's prime minister Ehud Barak and Arafat in 2000 remained deadlocked over Israeli-occupied East Jerusalem, which Arafat insisted must be the capital of the future Palestinian state. At the end of September, however, the stalemate disintegrated into the worst violence between Israelis and Palestinians in years, provoked by Likud hard-liner Ariel Sharon's visit to the compound called Temple Mount by Jews and Haram al-Sharif by Muslims. The compound is a fiercely contested site that is sacred to both faiths. The intensified violence, which included an unprecedented number of Palestinian suicide attacks against Israeli civilians and the inevitable Israeli military reprisals, was dubbed the al-Aksa intifada. In four years (2000–2004), the intifada had led to the deaths of almost 4,000, including nearly 3,000 Palestinians.

For five months in 2002, Israeli troops surrounded Yasir Arafat at the Palestinian Authority headquarters in Ramallah. Prime Minister Sharon, blaming Arafat directly for inciting terror, called for his expulsion from the territories. Washington echoed Israel's view that Arafat had become “irrelevant” and announced that the U.S. would not recognize an independent Palestinian state until Arafat was replaced. Throughout the summer, Palestinian suicide bombings (Hamas and the Al-Aksa Martyr Brigade claimed responsibility for the majority of them) and Israeli reprisals continued. In March 2003, Arafat agreed to political reforms: his government, to the disillusionment of many Palestinians, was rife with corruption. He also agreed to share power with a prime minister. Mahmoud Abbas, second-in-command of the PLO, assumed the post in April. Unlike Arafat, Abbas emphatically rejected the Palestinian intifada, but he had no influence or control over Palestinian militant groups the way Arafat did. On May 1, the Quartet (the U.S., UN, EU, and Russia) unfurled its “road map” for peace, which called on both sides to make concessions and end the wave of deadly violence. But the road map quickly led nowhere; Abbas, with little real political power, could not disable terrorist organizations, and Israel did not dismantle settlements, much less prevent new ones from cropping up. Sharon also continued to build the controversial security barrier that divides Israeli and Palestinian areas. Abbas resigned in September, and Arafat appointed a new prime minister, Ahmed Qurei.

Assassinations, a New Government, and a Temporary Withdrawal

On March 22, 2004, Israel assassinated Sheik Ahmed Yassin, the founder and spiritual leader of Hamas. In the previous six months, Israel had killed more than 20 Hamas officials and vowed to destroy the entire leadership. Within months, Israel had assassinated Yassin's successor as well.

In July 2004, Israel revised the route of its security barrier so that it no longer cut into Palestinian land. The UN estimated that the original route would have taken almost 15% of West Bank territory for Israel. The new route was also meant to limit undue hardships, such as separating Palestinian villagers from their farmland.

On Nov. 10, Yasir Arafat died, marking the end of an era in Palestinian affairs. On Jan. 9, 2005, former prime minister Mahmoud Abbas (also known as Abu Mazen) was easily elected president with 62% of the vote. At a summit in February, Abbas and Israeli prime minister Sharon agreed to an unequivocal cease-fire, the most promising move toward peace in the four years since the intifada began.

On Aug. 15, 2005, the withdrawal of some 8,000 Israeli settlers from Gaza began. Two years earlier, Sharon had announced his plan for Israel's unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip. In turn, Israel was to hold on to large blocks of land in the West Bank and reject the “right of return” for Palestinian refugees. The Israeli evacuation involved 21 Gaza settlements as well as four of the more isolated of the West Bank's 120 settlements. Gaza, which has the world's highest population density, gained 25% more land and plans on replacing the settlers' single-family houses with apartment buildings to alleviate a severe housing shortage. A private group of American philanthropists purchased 800 acres of greenhouses from the departing settlers and donated them to the Palestinians, preserving an important source of jobs and revenue in an area with 40% unemployment.

The Rise of Hamas

Palestinian elections on Jan. 25, 2006, resulted in a stunning and unexpected landslide victory for Hamas (74 of the 132 parliamentary seats) over the ruling Fatah Party, and in February, Ismail Haniya, a centrist Hamas leader, became prime minister. Most assessments indicate that Palestinians, weary of Fatah's mismanagement and widespread corruption, chose Hamas because it promised internal reform—Hamas's well-run social services network provides Palestinians with much-needed education and health care—and not because of its militant policies toward Israel. According to a PA poll, 75% of Palestinians who voted for Hamas supported a peace deal with Israel. Although Hamas had been engaged in a cease-fire with Israel for more than a year, it continued to call for Israel's destruction and refused to renounce violence. As a result, Western donor countries cut off direct aid to the Hamas-run government. By September, the humanitarian crisis was desperate, with 70% of Gaza's population lacking enough daily food.

In June, the yearlong cease-fire with Israel ended. After Hamas militants killed two Israeli soldiers and kidnapped another on June 25, Israel launched air strikes and sent ground troops into Gaza, destroying its only power plant and three bridges. Israel also arrested many of Hamas's elected officials. Fighting continued in July, with Hamas firing rockets into Israel, and Israeli troops killing about 200 Palestinians in June and July.

Hamas and Farah Clash

In Dec., after months of fruitlessly attempting to form a unity government, Hamas and Farah turned on each other. Street fights and shootings broke out between the various factions in Gaza for more than a week until a ceasefire called by President Abbas (Fatah) and Prime Minister Haniya (Hamas). In March 2007, the leaders of Hamas and Fatah finally agreed on a coalition government, which Parliament later approved. The platform that outlines the Hamas-dominated government does not recognize Israel, accept earlier Israeli-Palestinian accords, or renounce violence, conditions required by Western countries before they resume aid to the Palestinian government. Despite the breakthrough, Prime Minister Haniya and President Mahmoud Abbas remain divided on important issues regarding Israel.

Fighting between Hamas and Fatah intensified in June 2007, with Hamas effectively taking control of the Gaza Strip. In response, Palestinian president Abbas dissolved the government, fired Prime Minister Ismail Haniya, and declared a state of emergency. Salam Fayyad, an economist, took over as interim prime minister. In an effort to boost Abbas, the United States and the European Union said they will resume direct aid to the Palestinians.

Attempting Cease-Fire

At a Middle East peace conference in November hosted by the United States in Annapolis, Md., Israeli prime minister Olmert and Abbas agreed to work together to broker a peace treaty by the end of 2008. "We agree to immediately launch good-faith bilateral negotiations in order to conclude a peace treaty, resolving all outstanding issues, including all core issues without exception, as specified in previous agreements,” a joint statement said. “We agree to engage in vigorous, ongoing and continuous negotiations, and shall make every effort to conclude an agreement before the end of 2008.” Officials from 49 countries attended the conference.

After years of almost daily exchanges of rocket fire between Israelis and Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, Israel and Hamas, the militant group that controls Gaza, signed an Egyptian-brokered cease-fire in June. The fragile agreement held for most of the remainder of 2008. Israel continued its yearlong blockade of Gaza, however, and the humanitarian and economic crisis in Gaza intensified.

While Palestinian and Israeli officials continued their dialogue throughout 2008, a final peace deal remained out of reach amid the growing rift between Fatah, which controls the West Bank, and Hamas. In addition, Israel's continued development of settlements in the occupied West Bank stalled the process. The peace process was further jeopardized in December, days after the cease-fire between Israel and Hamas expired. Hamas began launching rocket attacks into Israel, which retaliated with airstrikes that killed about 300 people. Israel targeted Hamas bases, training camps, and missile storage facilities. Egypt sealed its border with Gaza, angering Palestinians who were attempting to flee the attacks and seeking medical attention. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert said the goal of the operation was not intended to reoccupy Gaza, but to “restore normal life and quiet to residents of the south” of Israel.

After more than a week of intense airstrikes, Israeli troops crossed the border into Gaza, launching a ground war against Hamas. Israeli aircraft continued to attack suspected Hamas fighters, weapons stockpiles, rocket-firing positions, and smuggling tunnels. After several weeks of fighting, more than 1,300 Gazans and about a dozen Israelis had been killed.

Abbas Under Fire

In Aug. 2009, Fatah held its first party congress in 20 years, on the Israeli-occupied West Bank. More than 2,000 delegates attended from all over the world. The party elected a slate of new blood to the Central Committee, a signal that the party is ready for change and eager to shed its reputation for corruption and cronyism that has weakened the party. Indeed, only four of the 18 delegates on the committee were reelected. New members include Marwan Barghouti, a popular leader who's serving several life terms in an Israeli jail. Former prime minister Ahmed Qurei was not reelected.

In Sept., Richard Goldstone, a South African jurist, released a UN-backed report on the conflict in Gaza. The report accused both the Israeli military and Palestinian fighters of war crimes, alleging that both had targeted civilians. Goldstone, however, reserved much of his criticism for Israel, saying its incursion was a "deliberately disproportionate attack designed to punish, humiliate, and terrorize a civilian population." Israel denounced the report as "deeply flawed, one-sided and prejudiced." The United States also said it was "unbalanced and biased," and the U.S. House of Representatives passed a non-binding resolution that called the report "irredeemably biased and unworthy of further consideration or legitimacy."

Goldstone recommended that both Israel and the Palestinians launch independent investigations into the conflict. If they refused, Goldstone recommended that the Security Council then refer both to the International Criminal Court. The UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution in October that endorsed the report and its recommendation regarding the investigations. In November, the UN General Assembly passed a similar resolution. Both Israel and the U.S. said continued action on the report could further derail the peace process.

Abbas announced in November that he would not seek reelection in January 2010's general and presidential elections, citing the protracted impasse between Israelis and Palestinians and the United States' failure to aggressively take steps toward negotiating a settlement. His poll numbers were on the decline for much of 2009, with militants angered by his ongoing discussions with Israeli defense minister and former prime minister Ehud Barak and his reluctance to use force against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. His popularity hit a new low in October, when he wavered in his response to the UN-backed Goldstone report.

Abbas initially seemed to have caved to a U.S. request that he not pursue further action by the UN in response to the report. Under intense pressure, however, with Hamas accusing him of betrayal, Abbas back-pedaled and said he would push to bring the matter before the Security Council. The U.S. and Israel had warned Abbas that doing so would further derail the peace process.

Palestinian Factions Sign Historic Reconciliation Accord

In May 2011, Fatah and Hamas, rival Palestinian parties for the last five years, signed a reconciliation accord. Before reconciling, the Fatah party, led by Mahmoud Abbas, governed the West Bank and Hamas, an Islamist movement, ran the Gaza Strip. The two factions cited the common cause of being against the Israeli occupation and disillusionment with American peace efforts as reasons for the reconciliation.

The deal, brokered by Egypt, remakes the Palestine Liberation Organization, which until now excluded Hamas. A unity government will be formed and an election date will be set. Hamas will be part of the political leadership, starting with a committee to study changes that need to be made. Hamas' new, larger role in the Palestinian government could have consequences. The United States, which recognizes Hamas as a terrorist group, currently provides hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to Palestine. Benjamin Netanyahu, prime minister of Israel, condemned the reconciliation.

Palestine Officially Requests Membership to UN

On May 16, the New York Times published an opinion piece written by Mahmoud Abbas. He stated that at the Sept. 2011 United Nations General Assembly, Palestine will request international recognition based on the 1967 border. The State of Palestine will also request full membership to the UN. He wrote that negotiations remained the Palestinians' first option, but "due to their failure we are now compelled to turn to the international community to assist us in preserving the opportunity for a peaceful and just end to the conflict."

On Friday, Sept. 23, 2011, Palestinian president Mahmud Abbas officially requested a bid for statehood at the United Nations Security Council. The request came after months of failed European and U.S. efforts to bring Israel and Palestine back to the negotiating table. Abbas followed up the request with a speech to the General Assembly in which he said, "I do not believe anyone with a shred of conscience can reject our application for full admission in the United Nations."

The Palestinian Authority is pursuing a Security Council vote to gain statehood as a full member of the UN rather than going to the General Assembly. One of the reasons for this is that the General Assembly can only give the Palestinian Authority non-member observer status at the UN, a lesser degree of statehood. In addition, the European states in the General Assembly have made it clear that they will support the proposal if the Palestinians drop their demand that Israel halt settlement construction. The Palestinians have long insisted that Israel cease the settlement construction and deemed the condition unacceptable. Therefore, the Palestinian Authority prefers to take its case to the Security Council even though the U.S. has vowed to veto the request.

Abbas's application to the UN Security Council is historic. It is a response to years of frustration with the stalled peace talks. The Security Council will most likely begin to examine the proposal next week while the U.S. and its allies work to stall it. Only time will tell if the bid helps make real progress in negotiations with Israel or becomes counterproductive. Patience meanwhile has grown very thin in Palestine as other countries in the region continue to overthrow old governments and attempt to forge ahead with new ones. While diplomats debate at the UN in September 2011, thousands of Palestinians rallied for statehood in Ramallah, home of the Palestinian government.

In Oct., Israel and Hamas reached a deal in which Gilad Shalit, a 25-five year old Israeli soldier who had been held in Gaza since Hamas militants kidnapped him during a cross-boarder raid in 2006, was released in exchange for more than 1,000 Palestinians who have spent years in Israeli jails. Israel and Hamas had made several fruitless attempts to negotiate such a deal. There were mixed reactions on both sides, with the Israelis thrilled about Shalit's release but upset by his frail appearance. The Palestinians accused Israel of torturing their prisoners and vowed to take more hostages. Israel also feared that the released prisoners would resume attacks on Israel. Some observers speculated that the compromise will help further the peace process. Others suggested that neither Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu nor Hamas had enough support—or the willingness— to return to the bargaining table.

Progress for UN Memberships Stalls

In Oct. 2011, UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) approved the Palestinian bid for full membership to the UN with a 107 to 14 vote. The favorable vote defied a mandated cutoff of American funding. The U.S. contributed $70 million to UNESCO a year. That was about 22 percent of its yearly budget. The vote made Palestine the 195th member of UNESCO.

However, by November, the prospect for full membership was looking doubtful for the Palestinians. In a Security Council meeting, France and Bosnia said they would abstain on a vote. That would leave the Palestinians short of the nine votes needed in favor of gaining full UN membership.

Full membership to the UN requires recommendation from the 15-member Security Council, with a nine vote majority and no veto from the five permanent members. A submission then goes to the General Assembly where it requires a two-thirds vote from its 193 members.

Exploratory Talks with Israel End while Unity Government with Hamas Moves Forward

In Jan. 2012, Israeli and Palestinian negotiators met in Jordan. Seen as an effort to try to revive peace talks, it was the first time the two sides had met in over a year. On Jan. 25, 2012, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas said that the discussions had ended without any significant progress. However, Abbas also said that there was a possibility talks would resume under certain conditions and after consulting with the Arab League in February 2012.

Also in Jan., Palestinians in the West Bank protested over climbing prices and recent tax increases. The demonstrators denounced Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. The protests prompted Fayyad to postpone the tax increases until mid-February in the hope that a solution to the tax issue could be found.

In Feb., Abbas and Hamas leader Khaled Meshal announced they had formed an interim unity government, which would be led by Abbas. The announcement marked an end to months of political deadlock. The unity government could threaten future negotiations between Palestine and Israel. Hamas has long rejected Israel's right to exists and is considered a terrorist organization by Israel, the United States and other countries.

On Feb. 29, 2012, Israeli troops along with officials from Israel's Communications Ministry raided two Palestinian television stations in the West Bank. The troops confiscated documents, hard drives and transmitters. Israel's Communications Ministry released a statement saying that the stations were using frequencies that blocked transmissions in Israel, a violation of Israeli-Palestinian agreements. The ministry said it repeatedly warned both stations before entering. Officials from the Palestinian Authority responded by condemning the raid, saying the television stations received no warnings and committed no violations.

Palestinian Authority Marks 19th Oslo Accords Anniversary with Economic Troubles

Sept. 2012 marked the 19th anniversary of the Oslo Peace Accords, an agreement that gave Palestinians self-rule with limits. The Oslo Accords were meant as a temporary, five-year arrangement where the Palestinian Authority would begin the process of establishing a Palestinian state. The arrangement outlines limits and procedures for economic and security measures between Israel and Palestine. However, those limitations threatened the future of the Palestinian Authority in the fall of 2012. The main issue was the economy. The authority needed $400 million in aid to help with their 2012 budget. Protests in Palestine increased throughout 2012 over the rising cost of living and fuel price increases. A lot of the protests were aimed at Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. "We are doing the best we can, and we have been all along," said Fayyad in response to the protests.

Sept. 2012 also marked the one year anniversary of Palestine's failure to win membership to the United Nations via the Security Council. The Palestinians returned to the U.N. General Assembly in late Sept. 2012 to seek status as a nonmember state.

Violence Erupts Between Israel and Gaza in November 2012

On Nov. 14, 2012, Israel launched one of its biggest attacks on Gaza since the invasion four years ago and hit at least 20 targets. One of those targets was Hamas military commander, Ahmed al-Jabari. He was killed while traveling through Gaza in a car. Al-Jabari was the most senior official killed by the Israelis since its invasion in 2008. The airstrikes were in response to recent, repeated rocket attacks by Palestinian militants located in Gaza.

The next day, Israel continued with the airstrikes against Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza. The Palestinian death toll rose to 11. Meanwhile, Hamas fired rockets into southern Israel, killing three civilians. The three Israeli deaths would likely lead to Israel increasing its military offensive in Gaza. Two long range rockets were aimed at Tel Aviv. They caused no harm, falling into the sea nearby, but an air raid warning went off in the city. In a nationally televised address, Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi said that his country would stand by the Palestinians. "The Egyptian people, the Egyptian leadership, the Egyptian government, and all of Egypt is standing with all its resources to stop this assault, to prevent the killing and the bloodshed of Palestinians," Morsi said in the address.

According to officials in Gaza, 19 people had been killed from the Israeli airstrikes by Nov. 16, 2012. Hesham Qandil, Egypt's prime minister, showed his country's support by visiting Gaza. However, his presence did not stop the fighting. Heavy rocket fire continued from Gaza while the Israeli military called in 16,000 army reservists. For the second time since 2008, Israel prepared for a potential ground invasion.

Throughout mid-Nov., Israel continued to target members of Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza while Hamas launched several hundred rockets, some hitting Tel Aviv. Egypt, while a staunch supporter of Hamas, attempted to broker a peace agreement between Hamas and Israel to prevent the conflict from further destabilizing the region. Finally on Nov. 21, Egypt's Foreign Minister Mohamed Kamel Amr, and U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that a cease-fire had been signed. Both sides agreed to end hostilities toward each other and Israel said it would open Gaza border crossings, allowing the flow of products and people into Gaza, potentially lifting the 5-year blockade that has caused much hardship to those living in the region.

UN Approves Non-Member State Status

On Nov. 29, 2012, the United Nations General Assembly approved an upgrade from the Palestinian Authority's current observer status to that of a non-member state. The vote came after Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas spoke to the General Assembly and asked for a "birth certificate" for his country. Of the 193 nations in the General Assembly, 138 voted in favor of the upgrade in status.

While the vote was a victory for Palestine, it was a diplomatic setback for the U.S. and Israel. Having the title of "non-member observer state" would allow Palestine access to international organizations such as the International Criminal Court (ICC). If they joined the ICC, Palestine could file complaints of war crimes against Israel. After the vote, Palestinian Foreign Minister Riyad al-Maliki spoke in a press conference about working with the ICC and other organizations. He said, "As long as the Israelis are not committing atrocities, are not building settlements, are not violating international law, then we don't see any reason to go anywhere. If the Israelis continue with such policy - aggression, settlements, assassinations, attacks, confiscations, building walls - violating international law, then we have no other remedy but really to knock those to other places."

In response to the UN vote, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that Israel would not transfer about $100 million in much-needed tax revenue owed to the struggling Palestinian Authority and would resume plans to build 3,000-unit settlement in an area that divides the north and the south parts of the West Bank, thereby denying the Palestinians any chance for having a contiguous state.

In Dec. 2012, Israel defied growing opposition from the international community by forging ahead with the building of new settlements. Israel's Housing Ministry approved various new settlements throughout the last month of 2012. Construction on them began immediately.

With the exception of the United States, every member of the United Nations Security Council condemned the construction, concerned that the move threatened the peace process with Palestine. At his year-end news conference, Ban Ki-moon, secretary general of the United Nations, said, "This gravely threatens efforts to establish a viable Palestinian state. I call on Israel to refrain from continuing on this dangerous path, which will undermine the prospects for a resumption of dialogue and a peaceful future for Palestinians and Israelis alike. Let us get the peace process back on track before it is too late."

Egypt Attempts to Get Hamas and Fatah to Reconcile

In early Jan. 2013, President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt invited Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas and Hamas leader Khaled Meshal to Cairo. First, Morsi met with each one individually. The objective was to work toward a reconciliation of the two factions, Fatah and Hamas, but according to officials, there was little progress.

After meeting with Morsi, Abbas released a statement, "We discussed the Palestinian conditions and the means to achieve reconciliation through implementing the agreed-upon steps according to the Doha and Cairo agreements." The Doha and Cairo agreements were pacts signed in 2012 by Fatah and Hamas. Abbas did not comment or release a statement after meeting with Meshal, another sign that there was little, if any, progress.

Prime Minister Salam Fayyad resigned in April 2013 amid infighting among the top echelon of the Palestinian Authority and popular discontent. Fayyad is credited with cracking down on corruption in the West Bank, improving infrastructure, and boosting the economy, which resulted in an increase in international aid. However, after Palestinian president Mahmud Abbas requested a bid for statehood at the United Nations Security Council, the U.S. stopped funding the Palestinian Authority and the economy soured. It was unclear how Fayyad's resignation would affect the reconciliation of Fatah and Hamas.

Rami Hamdallah Becomes Prime Minister

On June 6, 2013, Rami Hamdallah was sworn in as prime minister. Hamdallah was born in the West Bank. He graduated from the University of Jordan in 1980 and went on to receive his MA from the University of Manchester two years later. He also has a PhD in linguistics from Lancaster University. In 2011, three of his children were killed in a traffic accident involving an Israeli vehicle.

The president of An-Najah National University in Nablus, Hamdallah is a member of the Fatah party. His appointment to prime minister is not recognized by Hamas.

Peace Talks Resume After Five Years

On Aug. 14, 2013, Israelis and Palestinians began peace talks in Jerusalem. Expectations were low going into the talks, the third attempt to negotiate since 2000, and nearly five years since the last attempt. The talks began just hours after Israel released 26 Palestinian prisoners. The prisoner release was an attempt on Israel's part to bring Palestine back to the negotiating table. Israel said the prisoner release would be the first of four. Palestinian officials expressed concern about Israel's ongoing settlement building in the West Bank and east Jerusalem, land that would be part of an official Palestinian state.

Palestinian officials said they called off the peace talks after three protesters were killed by Israeli soldiers on Aug. 26, 2013. The clash between the protesters and soldiers happened after Israeli forces entered the Qalandia refugee camp, located outside of Jerusalem, as part of a nighttime arrest raid. After the raid, hundreds of Palestinians rushed into the streets to throw rocks, concrete and firebombs at the Israeli soldiers. Along with the three killed in the clash, more than a dozen others were wounded. The incident was the deadliest in that area near Jerusalem in years. Palestinian officials said the break in peace talks would be brief. Israeli officials did not comment. U.S. State Department deputy spokesperson Marie Harf said that "no meetings have been canceled. We've been clear that the two parties are engaged in serious and sustained negotiations."

Israel freed another 26 Palestinian prisoners as part of the current U.S.-brokered peace talks in October. However, soon after the prisoners were released, the Israeli government reported it planned to build 1,500 new homes in east Jerusalem, an area claimed by the Palestinians. The settlement announcement was seen as a concession to the right after the prisoner release. By Nov. 2013, peace talks appeared to be on the verge of collapse when a Palestinian negotiator said no deal would be better than one that allowed Israel to keep building settlements.

In late Feb. 2014, both U.S. and Israeli officials suggested that an extension on the peace talks deadline would be necessary. Palestinian chief negotiator Saeb Erakat rejected any extension. "There is no meaning to prolonging the negotiation, even for one more additional hour, if Israel, represented by its current government, continues to disregard international law." In his statement, Erakat referred to the continued Israeli construction on land it seized during the 1967 Middle East war, construction considered a violation of international law by Palestine and the international community.

When Israel failed to release the promised last batch of prisoners in late March 2014, U.S. Secretary John Kerry headed there in an attempt to rescue the latest round of peace talks. Israel had promised to release Palestinian prisoners in four groups and released the first three groups. But Israel's failure to release the last group of 26 prisoners as well as their continued settlement expansion in the West Bank threatened to derail a peace agreement that was supposed to be reached by the end of April 2014. Palestine said that the peace talks would end on April 29 if Israel did not release the 26 prisoners.

In April 2014, the troubled peace talks hit another snag when Palestinian leadership and Hamas forged a new reconciliation agreement. The new unity deal angered the Israeli government. Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reacted by saying that Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas was choosing "Hamas, not peace." The U.S. government warned that the new accord could prevent any progress in the Israeli-Palestinian peace talks. Since 1997, Hamas has been a designated foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department. On April 24, 2014, the day after the Palestinian leadership announced its new unity deal with Hamas, Israel responded by halting the peace talks. The following day, Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah resigned. The deadline for this latest round of peace talks passed without an agreement a week later.

Pope Francis invited leaders of Israel and the Palestinian Authority to come to the Vatican for what he called a "peace initiative." The invitation came while Pope Francis delivered an outdoor Mass in Bethlehem during his three-day trip to the Middle East in late May 2014. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas accepted the invitation from Pope Francis. Likewise, the office of Israeli President Shimon Peres responded that Peres welcomed the invitation. Both would travel at some point in the near future to the Vatican.

2013 Report Supports Theory That Arafat Was Poisoned

A new forensics report released by a team of Swiss scientists supports the theory that Yasir Arafat was poisoned. The 108-page report, published on Nov. 6, 2013, said that radioactive polonium-210 was found within Arafat's remains. The exploration of the matter began in Jan. 2012 when a reporter working for Al Jazeera English approached the University of Legal Medicine in Switzerland on behalf of Arafat's widow. Al Jazeera commissioned the forensic examination after providing the travel bag that Arafat had with him when he died. After finding "an unexplained elevated amount of unsupported polonium-210" in the bag, the Swiss team exhumed Arafat's body.

Russian and French teams worked with the Swiss to test the remains. The report took into account limitations such as the amount of time that had passed since Arafat died in Nov. 2004. However, even with limitations, the examination findings moderately supported the proposition that Arafat died from polonium poisoning. Therefore, the report supported the suspicions that Arafat's supporters have had since his death, that he was killed by rivals of Palestine or Israeli agents. Israel has repeatedly denied any involvement with Arafat's death.

New Unity Government Includes Hamas

The Palestinian government announced a new "government of national unity" on June 2, 2014. The new unity government, formed by Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah, included Hamas, considered a terrorist organization by Israel and the United States. The reconciliation agreement ended two separate governments in Gaza and the West Bank.

The new government would still be led by moderate Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Hamdallah and was considered a huge step toward ending the seven year battle between the two separate political factions in Palestine. In a televised speech, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas said, "Today we declare the end of the split and regaining the unity of the homeland. This black page in our history has been closed forever." Abbas also vowed that the new government was committed to continuing the course of nonviolence.

Murders of Israeli and Palestinian Teenagers Increases Tension

Later in June, three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped and killed while hiking in the occupied West Bank. Their bodies were recovered days later and a burial was held in early July. The day after their burial, the burned body of a missing Palestinian teenager was found in a forest near Jerusalem. The incidents increased tension between Israelis and Palestinians, including riots in East Jerusalem and an exchange of rocket fire in Southern Israel and Gaza, where Israel targeted Hamas. Prime Minister Netanyahu asked the Israeli police to investigate what he called "the abominable murder" of the Palestinian teenager in what may have been a revenge killing in reaction to the death of the three Israeli teenagers. Within a week, several Israeli Jewish suspects were arrested in connection with the killing of the Palestinian teen. Meanwhile, Hamas leaders praised the kidnapping and killing of the three Israeli teenagers, but did not take credit for the incident.

The situation continued to escalate throughout July. Hundreds of rockets were launched into Israel by militant groups in Gaza. The rockets reached areas in Israel that previous rocket attacks could not, such as outskirts of Jerusalem. In response, Israel launched an aerial offensive in Gaza, killing dozens of Palestinians, and called up thousands of reservists for a potential ground operation.

On July 17, 2014, Israel launched a ground offensive into Gaza. Israeli officials said that the mission's main focus was tunnels near Gaza's borders that were being used by Hamas to enter Israel. As the violence continued and the casualties mounted on both sides, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry pressed Egyptian, Israeli, and Palestinian leaders to negotiate a cease-fire. In the midst of his urgent diplomatic outreach, 16 Palestinians were killed and more than 100 wounded in an attack on a UN elementary school in Gaza on July 24. Israel denied launching the attack, saying Hamas militants were responsible, missing their target. Demonstrations followed the attack, and Palestinians in the West Bank protested to show unity with Gazans. At least five protesters were killed by Israeli fire.

The UN Security Council issued a statement on July 28 calling for a humanitarian cease-fire. Later that day, a hospital and a refugee camp in Gaza were hit, killing about 10 children. Israel blamed the attack on a "failed rocket attacks launched by Gaza terrorists," and Hamas said the sites were hit by Israeli drones.

After fighting for seven weeks and attempting several short-term cease-fires, Israel and Hamas agreed to an open-ended cease-fire on Aug. 26. The agreement was mediated by Egypt. The interim agreement still had Hamas in control of Gaza while Israel and Egypt still controlled access to Gaza, leaving no clear winner in this latest conflict. However, Hamas declared victory. Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was criticized in Israel for how costly the conflict has been. Since the conflict began in early July, 2,143 Palestinians were killed, mostly civilians, with more than 11,000 wounded and 100,000 left homeless. On Israel's side, 64 soldiers and six civilians were killed.

Britain Votes to Recognize Palestine

On Oct. 13, 2014, Britain's Parliament voted 274-12 to give diplomatic recognition to Palestine. The symbolic nonbinding vote was an indication of the British government's shift since the recent conflict in Gaza, the latest round of failed peace negotiations, and Israel continuing to build settlements. Earlier in Oct., Sweden became the first major Western European nation to recognize Palestine. During his inaugural address, Sweden's Prime Minster Stefan Lofven made the announcement. In his speech, Lofven said to Parliament, "the conflict between Israel and Palestine can only be solved with a two-state solution, negotiated in accordance with international law. Sweden will therefore recognize the state of Palestine."

Two Palestinians, armed with knives, meat cleavers, and a handgun, entered a synagogue in Jerusalem during morning prayers and killed five people on Nov. 18. Four of the people killed were rabbis; the other was a police officer who died hours after the incident. The two attackers were shot and killed by police. It was the deadliest assault that occurred in Jerusalem since eight students were killed during a Jewish seminar in March 2008. Hamas praised the synagogue attack, claiming it was in response to the recent death of a Palestinian bus driver. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas condemned the attack. In a televised address, Netanyahu said that Abbas' condemnation wasn't enough. Israel said it would retaliate, beginning with demolishing the homes of the synagogue's attackers. As 2014 came to a close, the incident increased tension in Israel, which was already on high alert after a recent rise in religious violence.

Palestine Asks to Join the International Criminal Court

On Dec. 30, 2014, a draft resolution which would have set a deadline to establish Palestine as a sovereign state failed to pass the 15-member U.N. Security Council. Jordan introduced the resolution for the Palestinians. The resolution set a one-year deadline for Israel to negotiate and asked for a full withdrawal of Israeli forces by 2017. Eight countries voted in favor of the measure, including Russia, China, and France. However, nine votes were needed to adopt the measure. The United States and Australia voted against it while Britain and the four other remaining nations abstained.

In reaction to the failed measure, the following day, Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas asked the International Criminal Court to let the Palestinian Authority join it. "There is aggression practiced against our land and our country, and the Security Council has let us down - where shall we go? We want to complain to this organization. As long as there is no peace, and the world doesn't prioritize peace in this region, this region will live in constant conflict. The Palestinian cause is the key issue to be settled," Abbas said of the court as he signed the court's founding charter, the Rome Statute, from his office in Ramallah.

The move could lead to even more conflict in the Middle East, including the possibility of Israeli officials being prosecuted by the court for war crimes. Abbas promised to continue the work to make Palestine a legal state, including resubmitting the U.N. Security Council resolution that failed. As of Dec. 2014, 135 countries officially recognized Palestine.

More Obstacles Emerge for Palestine in 2015

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his Likud Party won the March 2015 Israeli elections. The win for Likud meant that odds were highly in favor of Netanyahu serving a fourth term as prime minister. Netanyahu must form a government, a task which could be harder after he vowed leading up to the election that no Palestinian state would be established while he was in office, a vow that insulted Arab citizens and alienated some political allies.

After a backlash, Netanyahu backtracked from his pre-election statements against an establishment of a Palestinian state. In a March 19 TV interview, he said that he remained committed to a two-state vision and Palestinian statehood if conditions in the region improved. "I don't want a one-state solution, I want a sustainable, peaceful two-state solution, but for that circumstances have to change," Netanyahu said in the interview two days after the election.

In June 2015, President Abbas accepted the resignation of the Palestinian unity government. The unity government resigned after a meeting between Abbas and Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah in Ramallah. However, President Abbas asked Hamdallah to form a new government.

During the first two weeks of Oct. 2015, 32 Palestinians and seven Israelis were killed in what was the biggest spike in violence the area has seen in recent years. The violence broke out in part over what the Palestinians saw as increased encroachment by Israelis on the al-Aqsa mosque on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, a site important to both Muslims and Jews. However, the violence quickly spread beyond Jerusalem.

On Oct. 16, at the request of council member Jordan, the United Nations Security Council held a meeting to discuss the area's increasing unrest. During the meeting, France proposed that an international observer be placed at the al-Aqsa mosque, but that idea was rejected by Israel. Meanwhile, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry called for Israeli and Palestinian leaders to meet and agree on a plan to stop the violence.

Palestinian hurls a stone in clashes with Israeli troops,

near Ramallah, West Bank, Oct. 2015

Source: AP Photo/Majdi Mohammed

See also Encyclopedia: Palestine